PNB by the Decades: 1980s at PNB, the Origins of Kent Stowell’s Swan Lake and Nutcracker

Written by Zoe Meadows-Sahr

PNB took tremendous leaps toward establishing itself as an acclaimed ballet company in the 1980s. As the company grew artistically, it was compelled to grow administratively. More and more staff were hired, which led to an important physical move for the company. PNB’s original productions of Swan Lake and the Nutcracker, which both premiered in the ‘80s, were pivotal steps in this dance toward success. As PNB celebrates our 50th Anniversary, step back in time with us to our twentieth year and the very beginnings of some of our favorite productions!

Stowell’s Swan Lake

Kent Stowell’s Swan Lake, which premiered in 1981, was the first of these monumental productions. Stowell drew on a version he had first created for the Frankfurt Ballet with Francia Russell in 1976. Stowell and Russell were quite the dynamic duo, working together as co-artistic directors first at Frankfurt Ballet and then at PNB. Together, they decided to restage the Swan Lake they had developed in Frankfurt at PNB. Stowell made many important choreographic and narrative decisions in his Swan Lake production, most notably changing the ending from a tragic trio of death to a tender pas de deux. Russell, drawing on her years of experience as a stager for George Balanchine’s works, taught the PNB dancers Stowell’s choreography in the style of Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. With these artistic elements in place, the young company had to raise $360,000 total to pay for the sets, costumes, and salaries of the employees. Thanks to the tremendous effort of John E Iverson, president of the PNB board, and the generosity of Roland Tranfton, CEO of Safeco, PNB managed to raise the funds they needed. With all these elements in place, Swan Lake was ready to take the stage.

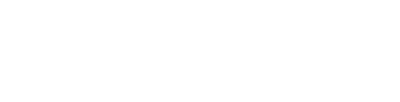

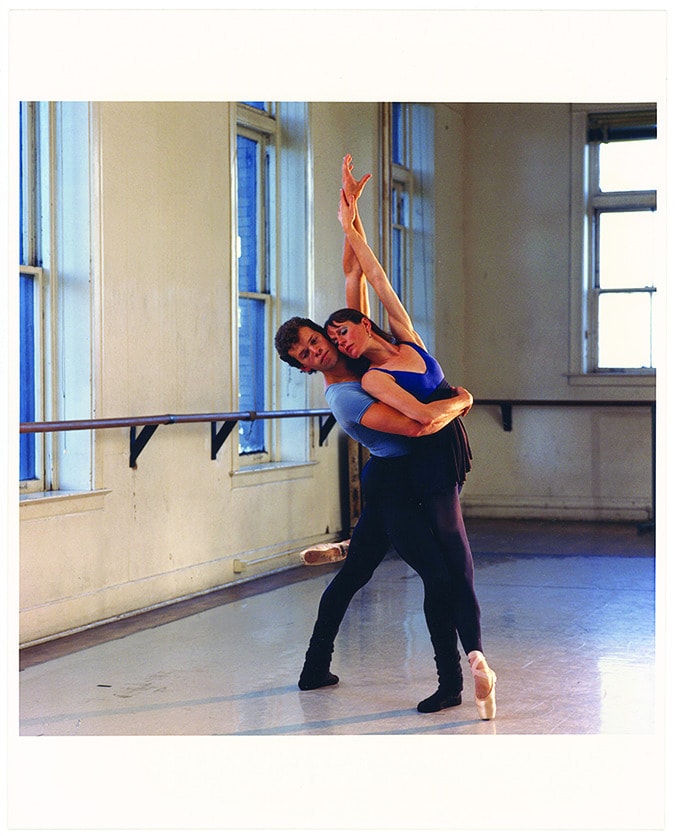

The steps were choreographed. The money was raised. The stage, as they say, was set. Now, the success of the production was up to the dancers’ performance and the audience’s reaction. On opening night, PNB, still relying on big-name ballet stars to drum up interest in performances, hired Gelsey Kirkland and Patrick Bissell to perform the principal roles. To everyone’s shock, Kirkland fell to the ground during the infamous thirty-two fouette section of Act III. PNB dancers Deborah Hadley and Jory Hancock (pictured to the left in 1981) performed the next night with excellent technique. Suffice it to say, Swan Lake was the last time PNB ever hired visiting artists to star in their productions! Seattlites praised PNB’s “homegrown” dancers, and dance critic Jon Blake of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote that PNB was “on the edge of national stature.”

Stowell and Sendak’s Nutcracker

Stowell and Russell were not done creating magical story ballets for PNB just yet! In 1981, the same year Swan Lake premiered, they began planning their very own version of The Nutcracker. After two years of working on the Christmas classic, Nutcracker premiered at PNB in 1983.

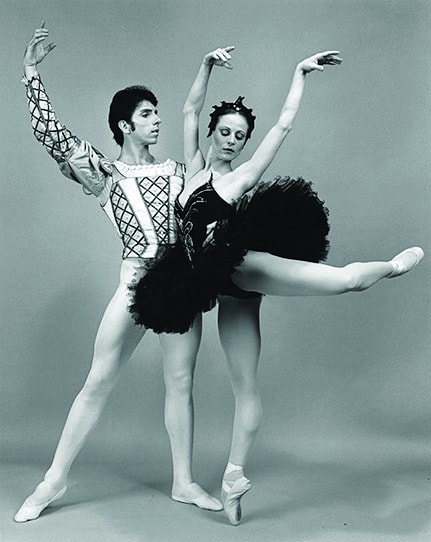

Stowell and Russell’s idea to create an original Nutcracker all began when Russell read a New York Times article about children’s book author Maurice Sendak’s sets for the opera The Magic Flute. Like many parents of the time, Stowell and Russell were familiar with Sendak’s genre-bending picture books like Where the Wild Things Are. Russell thought it would be “incredible to have Sendak’s kind of imagination” reimagine the Nutcracker. Stowell agreed and arranged to meet with Sendak in New York City. At first, Sendak was hesitant to work on Nutcracker. He felt it was a story so steeped in tradition that it was tired and overdone. Stowell convinced him that together they could create a version that was completely fresh, unique, and exciting. Over the next two years, Sendak and Stowell traveled from Seattle to New York to create their innovative Nutcracker.

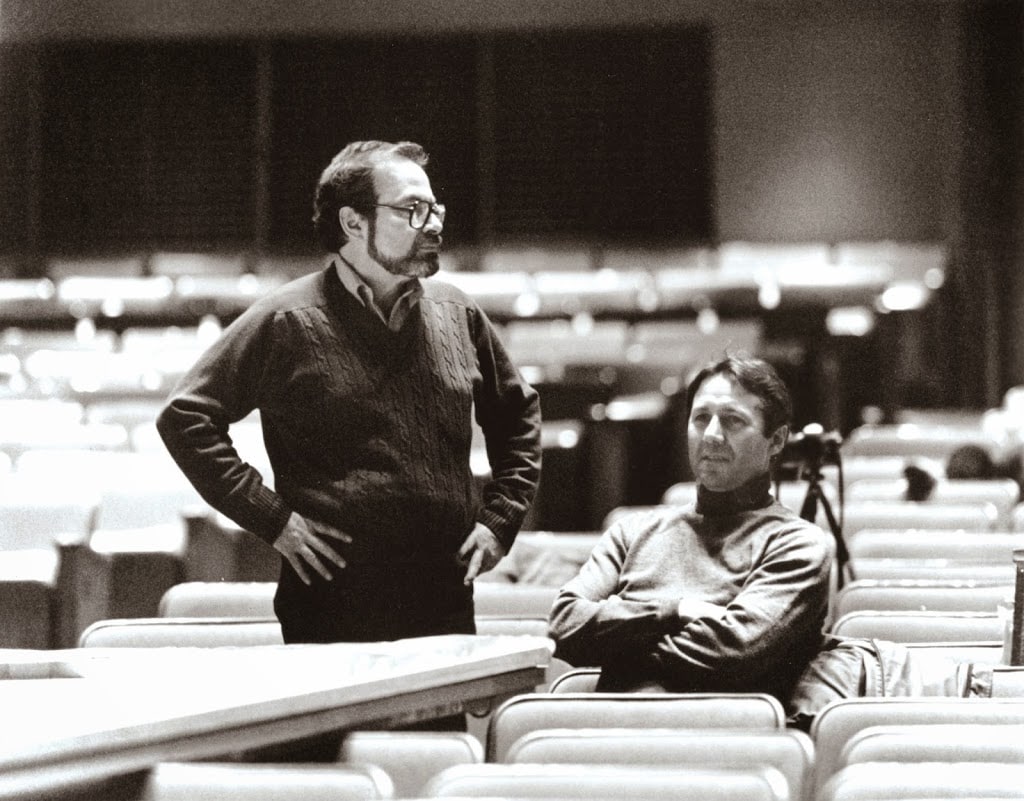

Bringing Maurice Sendak’s set designs to life was a feat for the still-small PNB, which raised just $200,000 for the project. Parts of the set were completed all over North America; for example, some scenery was built in San Fransisco and painted in Toronto. The famous Nutcracker Christmas tree, which grows and grows in Act I of the ballet, was built in New York. The tree was so large and unwieldy that it took two and a half days to load into the theater and nine stagehands to operate it at every show! Randall G. Chiarelli, who oversaw the entire process of creating the Nutcracker sets, said the audience had a mood of “consternation, awe, and sheer terror” watching the tree grow on stage. Once every extravagant set element was constructed, PNB ended up spending $600,000. With costs severely over budget, sales needed to get cracking!

Overspending wasn’t the only burden PNB faced while preparing for the Sendak and Stowell Nutcracker. At dress rehearsal, the company was finally ready to perform. Quickly, the dancers discovered the floor, which had been painted by an out-of-town shop, was too slippery to dance on. The shop had used incorrect materials not suitable for the pirouetting of a Sugar Plum Fairy or the lunging of a Mouse King. PNB stage painters started repainting the floor at 11:00PM that night and finished at 7:00AM on opening night. After a whirlwind of choreographing, building, rehearsing, and more, the stage was finally set (and dry). It only remained to be seen if the audiences would love the show.

As any PNB fan can guess, Sendak and Stowell’s Nutcracker was a huge success! Audiences loved the lavish sets and unique choreography. The first run of the production raised over 1.2 million, amply covering the unexpected additional production costs. Nutcracker attracted all new audience members to PNB, with most of its twenty-six shows reaching 99% capacity. Every facet of PNB’s staff, from the company dancers to the production crew, contributed a tremendous amount of time, effort, and talent, and it showed. In the words of Kent Stowell, “Nutcracker marked the end of PNB as a naïve, innocent organization.”

The Construction of PNB’s current home the Phelps Center

With all of this artistic growth came administrative growth. As PNB mounted larger and larger productions, a larger administrative team was required. In 1984, Jerome Sanford became PNB’s first executive director and then their first paid president. Arthur Jacobus was hired as CEO of the company in 1984. Jacobus said, “What I came to was a highly respected company, rather young and with not very well-developed organizational processes and staffing, but there was a good foundation on which to work. Over time, because of the increasing prestige of the company and the increasing ability to sell tickets and raise funds, we were able to build a strong administrative staff…” As the administrative staff continued to grow, a pressing need for more space for the company arose.

At the time, PNB was located at the Good Shepherd Center, which featured only two showers, cramped dressing rooms, and four dance studios. The three development staff, three marketing staff, and three accounting staff all shared one office. As more administrative staff were hired, it was clear that there wasn’t any room for them! PNB started exploring relocating the company in 1982. Ewen Dingwall, director of Seattle Center, suggested renovating the Exhibition Hall. The Exhibition Hall was an unused building constructed as part of Seattle’s World’s Fair with 40-foot ceilings and an open floor plan. Dingwall proposed cutting the space in half horizontally, using the upper half for PNB and the bottom for Seattle Center events. This arrangement was ideal for both PNB and Seattle Center, and the proposal was agreed to. PNB began a campaign in 1988 to raise $10,000,000 to renovate the building. After much effort and generosity, that campaign was successful, and construction finally began on the new building in March of 1991.

PNB had grown considerably throughout the ‘80s. As Wendy Griffin, a board chairman, said, in the early ’80s, “PNB was probably not prioritized very highly among Seattle arts institutions. That was natural because it hadn’t been around very long. But the fact that Nutcracker was so tremendously successful inspired not only the board but the community because the company had demonstrated its ability and its right to stand with other major cultural institutions in Seattle and to have its own home.” In 1985, PNB was awarded a National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) grant for $500,000, the largest amount the NEA had ever awarded to a company outside of New York City. Then, in 1987, PNB was voted the best-managed major arts organization in Seattle by the Corporate Council for the Arts. On all fronts, artistic and administrative, by its twentieth year, PNB had established itself as a major arts institution.

Photos: Jory Hancock and Deborah Hadley in Swan Lake, 1981 (photographer: John Turner). Maurice Sendak and Kent Stowell at the Seattle Opera House during a Nutcracker rehearsal. The Nutcracker tree backstage. Maurice Sendak, Alaina Albertson, and Kent Stowell take a bow at the Nutcracker premiere, 1983. Benjamin Houk and Deborah Hadley rehearse at the Good Shepherd Center, 1987.

Sources: Becker, Paula. “Pacific Northwest Ballet.” Historylink.org. June 20th, 2012. https://www.historylink.org/file/10135; City of Seattle. “Century 21 World’s Fair.” Seattle.gov. Last accessed May 26, 2023. https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/exhibits-and-education/digital-document-libraries/century-21-worlds-fair; Dietrich, Sheila. “A History of Pacific Northwest Ballet.” PNB Files. Last accessed May 26, 2023; Dietrich, Sheila. “Pacific Northwest Ballet: A Brief History.” PNB En Face Magazine. September, 2022. https://playbills.artslandia.com/pacific-northwest-ballet-carmina-burana-2022-en-face/full-view.html; Johnson, Wayne. Let’s Go On: Pacific Northwest Ballet at 25. Seattle: Documentary Book Publishers. 1997