While Jerome Robbins is best known in popular culture for this innovative work in Broadway musicals, such as On the Town, Gypsy, The King and I, Fiddler on the Roof & West Side Story, for which he received two Academy Awards in 1961, his first love was ballet. His career began as a dancer and his first successful musical, On the Town, was based on his wildly successful ballet Fancy Free about three sailors on shore leave in New York City, which he choreographed in 1944.

And though he choreographed 16 musicals, some of which he also conceived and directed, he would choreograph over 65 ballets throughout his career. One of the most successful of these 65 works is his Dances at a Gathering, which was created in 1969 after a ten year absence from the ballet world. Upon returning to the New York City Ballet studios creativity flowed from him in such a way that a work that was originally intended to be a short duet transformed into nearly an hour long ballet for five couples.

Even before the premiere, there was foreshadowing of the success to come. Jerry was worried that the piece was already too long at 25 minutes when he invited George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein to view a rehearsal; however, after the rehearsal Balanchine said, “Make more, make it like peanuts.” Robbins would later repeat this story to reporters, substituting ‘popcorn’ for ‘peanuts’ while mimicking a movie-goer shoveling popcorn in their mouth, unable to stop.

After the first performance it was evident that he had been successful in making the equivalent of delightfully addictive snack, which left audiences wanting more. After the premiere, Balanchine came backstage and kissed him on both cheeks, which was a first. The critics were happy too. Clive Barnes wrote in the New York Times:

“It is as honest as breathing, as graceful as lark song, and in some very special way more a thing to be experienced than merely just another ballet to be seen… He (Robbins) uses the music to surprise us with oxymoronic juxtapositions of poetry. You have to laugh sometimes at his sheer damnable cleverness, yet the laughter is ringed with admiration.”

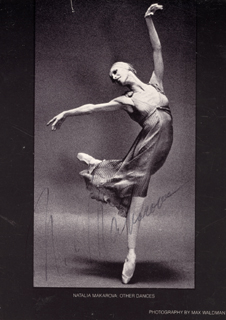

The ballet marked a creative peak for the choreographer, having crafted a masterpiece in a new style, both casual & romantic, which has been emulated by choreographers ever since. Jerry even expanded upon it in both In the Night and Other Dances, also set to the music of Chopin. This new naturalistic style was in part produced from the constraints of the New York City Ballet dancers’ demanding schedules, requiring them to rehearse during the day and perform at night. Since they often had to conserve their energy for the evening performances, they would often mark, or simply indicate the steps, during rehearsals. Though this would frustrate Robbins at times, he was ultimately inspired by it and incorporated it into the work. For example, after seeing the thoughtfulness with which Edward Villella marked his solo in one of the last rehearsals before the premiere, Jerry went up to him and said, “Now that’s what I want.”

Audiences also saw hints of narrative in the work, which made them wonder about its story and intention behind it. This work and many of his other abstract works also had this quality. In her memoir, ballerina Natalia Makarova remarks on his work, saying:

“For me, Jerry Robbins is the most romantic of all the neoclassical choreographers. On the surface he is like Balanchine, working primarily in the genre of plotless ballet, but the degree of abstraction is not as great with Robbins. He is less geometric and for me is more poetic, because in his choreography there is always room for self-expression. I do not feel I am a mere instrument following precisely the prescribed design. Besides, though Jerry’s ballets do not have traditional plots, they always have something reminiscent of one, which is hard to articulate in a logical way.”

Despite this observance, Jerry would often deny this. In responding to a publication on Dances at a Gathering in Ballet Review, he wrote:

“For the record, would you please print in large emphatic and capital letters the following: THERE ARE NO STORIES TO ANY OF THE DANCES IN ‘DAAG.’ THERE ARE NO PLOTS AND NO ROLES. THE DANCERS ARE THEMSELVES DANCING WITH EACH OTHER TO THAT MUSIC IN THAT SPACE.”

However, there were other times when he would slip and give some insight as to his inspirations and intentions. It is evident that the piece was very much about a community, relationships, and enjoying the interactions that arise from them. And though he consistently said that the dancers on stage were not characters, but rather simply portraying themselves, under the surface of their seemingly joyful interactions there brooded something deeper and possible darker, which gave the piece significance beyond mere abstraction. This could be in part due to the fact that the piece was being made after the horrors of World War II and in the wake of the escalation of the Vietnam War. In a personal letter to a friend, Jerry wrote:

“I’ve had such a wonderful time working on it—never have I enjoyed work more. The result may surprise people in that it is romantic, lyric, sensuous and delicate—not punchy and sharp and dramatically or theatrically effective as my other works are. But it’s theater, and celebrates love and being and togetherness—a rather astonishingly optimistic view in face of today’s fearsome events.”

Additionally, in his autobiography, Prodigal Son, Edward Villella recalls Robbins coaching him in a rehearsal for his solo, saying:

“It’s as if it’s the last time you’ll ever dance in this theater, in this space. And this is your home, the place you know. It’s familiar, and I don’t want to overstate it, but it’s almost as if the atom bomb is going to fall. Everything is going to change.”

Finally, when asked about the ending moments of the ballet in which one man kneels and places his hand on the earth as the other cast members look into the auduence as if into the horizon, Robbins said:

“If I had to talk about it all, I would say that they were looking at… the clouds on the horizon which possibly could be threatening, but then that’s life, so afterwards you just pick up and go right on again. It doesn’t destroy them. They don’t lament. They accept.”

Though he has been adamant that there is no story, one can feel the weight of his thoughts as the dancers weave their way through the work, imbuing it with a feeling of nostalgia and sense of perseverance, possibly in the face of an impending threat. Together, these universal themes combined with musical wit and a distinctly naturalistic & American style, the ballet remains relatable and relevant almost 50 years after its creation.

Don’t miss PNB’s performances of this masterpiece at McCaw Hall September 22 27 & 28 @ 7:30 PM and September 29 @ 2:00 PM.

Featured photo: Lucien Postlewaite in Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering, photo © Angela Sterling.